A Porpoise Named Peppa

When Emma Elobeid stumbled upon the carcass of a harbour porpoise on an Isle of Wight beach, she decided to investigate.

How did it die? Why did it die? Who was supposed to remove it? Did anyone care? In a two-year quest for answers, she learns of the local impacts of global climate change and witnesses the worldwide biodiversity crisis wash up on her home shores.

Along the way, she hears shocking accounts of wildlife as waste and uncovers a lack of public health surveillance experts warn could unleash new and emerging zoonotic diseases.

This is not just a story about one stranded cetacean, but of compassion, complexity, climate, and community.

On 17th September 2020, I went looking for sea glass and found a body.

Balancing my tea – moderately gritty thanks to my then three-year-old's overly enthusiastic panning technique – on the pebbles, I joined said toddler in his hunt. Backed by buckthorn, we scoured the beach for water-worn jewels in mutual concentration.

My son broke the trance.

“Mummy,” he said.

“That dolphin is a bit broken.”

Eyes raised on impulse. Three or four metres from the incoming tideline was a mass of grey different to the grey of the turn-of-season water.

A fin. A face.

Hard to tell at first whether this finned, faced, something was moving in the water or because of it. With every breaking wave the creature hulked closer, and it became apparent that the motion had been misleading. This dolphin was, to quote the boy, quite broken.

Its skin, which from a distance had seemed pearlescent, had, on closer inspection, started to come away from its body like one of those cheap chemical foot peels. It heaved to a full stop at my feet, which had carried me to the tideline of their own accord.

Dead 'dolphin' at Priory Point, St. Helens, September 2020

Dead 'dolphin' at Priory Point, St. Helens, September 2020

Though I'd lived on the Isle of Wight for six years, this was the first time I had seen a dolphin – dead or otherwise. Until now, my cultural references to marine mammals revolved around classic cinema and childhood crushes: from Jesse in Free Willy to a young Elijah Wood in Flipper.

Drawing on his own cultural cache – Julia Donaldson’s Snail and the Whale – my son suggested we call a fire engine. I suspected it might be a bit late for that. But the boy had a point: someone needed to call somebody.

Edging up the shingle bank still facing the creature – it felt disrespectful to turn my back on it now – to my rucksack (pink and white, Jansport, 20 years old, recently recovered from the back of the hall cupboard), I foraged in the front Discman pocket for my iPhone.

Googling [“dead dolphin” + “Isle of Wight”] for the first – but not the last – time I am struck by the volume of results: 1,700 unique hits with as many images. I scan the locations, assuming much of the content to be aggregated. But no: Dead dolphin washed up at Sandown, Dead dolphin discovered at Shanklin. Dead dolphins at Bonchurch, Brighstone, Blackgang, Brook.

Three pages in, I click through to a Facebook page for a local marine charity and make a call.

At home, my more pragmatic husband – who has been receiving regular Whatsapp updates – does the same, to the Isle of Wight Council. As I wait for the arrival of action in either form, I stand guard over what I have very quickly come to think of as my dead dolphin.

It shifts slightly – or, rather, is shifted – and comes to rest shoreside. The beach is quiet but not empty. Now and then I reluctantly take on the role of temporary signposter: “It’s been reported!” I hear myself saying to a dog walker; “Someone is coming!” I call out to a jogger who has slowed at the spectacle; “The appropriate agencies have been informed!” I say to a couple who have turned the corner from Priory Bay and stumbled upon a toddler eyeing a corpse.

‘Captain’ Garry Oates, the founder of Blue Seas Protection, beats the Council to it. By two whole days, as it turns out.

He arrives wearing a fluorescent jacket; the universal uniform of authority. I must be further along the beach than I had described on the phone. There are an awkward few minutes in which I know that it is him approaching (on account of the yellow vest) and he knows it is me in waiting (on account of the dead dolphin) but the point between seeing and greeting is protracted by the size of the pebbles which make walking on this part of the beach an inelegant affair.

On final approach, he sees the dolphin and wrings his hands in an expression of torment at odds with his workmanlike demeanour. “Oh it’s terrible,” he says, sea-weathered eyes and accent marking him as Marriner material. “So sad.” He wipes away a tear (or sand). “Poor thing.”

He then tells me three things. First, my dead dolphin wasn’t a dead dolphin after all, but a dead porpoise. Second, porpoises (along with whales and dolphins) belong to a group of marine mammals called cetaceans – not to be confused with crustaceans. Finally, this particular porpoise was almost certainly a victim of bycatch. Between the wind and the waves, I mishear this as ‘by cwytch’, conjuring confusing images of death by underwater Welsh cuddles. Luckily I keep this to myself and all is explained.

Gesturing out to sea where a France-bound Brittany Ferry and a Portsmouth-bound container ship are passing behind St. Helens Fort, Captain Garry Oates tells me that commercial trawlers have once again been illegally active in the English Channel.

He explains how these giant industrial vessels drag miles of weighted nets along the seabed, indiscriminately hauling in tonnes of fish along with anything else that happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time: seabirds, turtles, debris, waste. Cetaceans. In the fishing industry, these accidental captures are known as bycatch. Despite its incidental sounding name, bycatch is brutal.

Captain Oates relays a gruesome tale in which workers aboard commercial trawlers roughly cut trapped cetaceans to save not these sentient marine beings, but their own nets. Some sink back into the ocean. Others drown and eventually wash ashore. It is a tale that is at once appalling and abstract. This was not why I came down to the beach today. Still, it lands: in that part of the Motherbrain that allows information to float and fester.

That evening, after reading a bedtime Snail and the Whale with a fresh sense of sobriety, I open my laptop. Sure enough, over the past few years some of the world’s largest trawlers had been spotted fishing in waters off the Isle of Wight: Dutch-registered 126 metre-long ‘Afrika’; 143 metre-long ‘Margiris’, weighing over 9,000 tonnes and banned from Australian waters; 86 metre long German-owned factory trawler ‘Annie Hillina’. One Tik-Tok tangent and several YouTube sessions later are enough to convince me that the horrors of bycatch are real. Garry’s claims hold up: in 2019, The Guardian reported a record number of mutilated dolphins washed up along the French coast, suspected slaughtered by the crew of commercial trawlers. I switch back and forth between these pictures and my camera roll, zooming in to point of pixelation: was that a gash from a rock or a wound from a rope? That laceration there – did it look linear and knifelike or jaggedly accidental? Was it too late to say?

My dead porpoise: the underbelly

My dead porpoise: the underbelly

For the next few weeks, I lose myself down a rabbit hole of marine traffic tracking, secretly hoping for a ‘gotcha’ moment that would allow me to trace my dead porpoise back to a single vessel. But there is not a trawler in trace: only a steady stream of cargo carriers, sailing boats, and crisscrossing cruise liners – plus a handful of high-speed vessels and end-of-season pleasure craft.

I was involved now. Somehow, I was going to find out what happened to my porpoise.

I enthusiastically regaled as much in my weekly MA journalism seminar. “How interesting,” my tutor says. “And how do you think you might move that along?”

I say all the ideas and hope one sticks: I could infiltrate a trawler, join Greenpeace on patrol, uncover a global network of marine murderers and map it all out on a piece of ultimately award-winning data journalism.

“You could…” she says slowly, not wanting to break my spirit nor fan my flame in a dangerous direction. “But a better first step might be talking to some experts.”

If you’re in the market for an expert on the causes of cetacean deaths, as I was, the internet will deliver you Rob Deaville. He is, quite literally (so says his Twitter handle) The Strandings Man.

Rob has managed the UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) for 16 years. Jointly funded by DEFRA, the Scottish and Welsh Governments, their official remit is to monitor cetacean strandings around the UK coast and investigate them post-mortem.

We talk on Zoom. It is November 2020 – the middle of a second national lockdown – and carcass collections have been temporarily suspended. In any case, my dead porpoise was judged too decomposed to warrant the round trip from CSIP HQ at the Zoological Society of London.

Evidence, like skin, disintegrates. CSIP funding only enables them to examine between 100 and 150 strandings per year – a mere fraction of the whole – and so they must prioritise only the freshest specimens of the most critical species. My porpoise doesn’t make the cut.

Still, I am keen to get his take on how she (that assumed shipwreck she) might have died. By now I have done my research: enough to know, at least, that bycatch is the leading cause of cetacean deaths worldwide. In the UK alone, according to a joint study by the WWF and Sky Ocean Rescue, three harbour porpoises die in fishing gear every day – over a thousand annually.

Was that it, then – case closed, story over before it began?

Not necessarily, says Rob Deaville The Strandings Man. “Yes, there are the fairly obvious direct Anthropogenic drivers of mortality - things like bycatch and ship strike. But there are also Anthropogenic drivers which are indirect like exposure to marine pollution, climate change, and so on. And then there are the natural drivers of mortality – harbour porpoises might be attacked by bottlenose dolphins or predated on by grey seals. Cetaceans face multiple threats: some of which are natural and some of which are unnatural. That’s what we’re here to find out.”

The angles widen. In time, I talk to other experts closer to home. Each tells me a variation of this same inconvenient truth. A marine biologist will caution me against over extrapolation: “It’s easy to assume that there’s some kind of mass event” he says, referring to impassioned individuals of local nature Facebook groups. “But a lot of strandings are very badly decayed, have come from hundreds of miles away, and have nothing to do with the seas locally.” A marine mammal medic responds with a sigh – and the sigh says “how long’s a piece of string?”

The question that now anchors my quest for answers isn’t so much “what killed the porpoise?” but “what didn’t kill the porpoise?”

It’s an uncomfortable place for an early-career journalist to be. I know that I should embrace this state of messiness which others call nuance, but I can’t seem to shake that editorial voice on my shoulder: “Drop and give me a nutgraf” and “A topline – once more with feeling!”

I feel like I should set the scene. The Isle of Wight is the largest island in the UK, some fifteen miles off the largest island in Europe. But the shape, substance, and statutes of the water which surrounds it are slippery.

Over 300 square kilometres of its waters are theoretically protected by an underwater array of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs). Each denotes a site of special interest: some for their marine megafauna, some for their nationally scarce seaweed, others because of their vital subtidal sand and sediment habitats. Priory Point – the stretch of beach between St. Helens and Priory Bay proper – where I found my porpoise is part of the Bembridge Marine Conservation Zone; a vital breeding ground for starfish, short-snouted seahorses, and stalked jellyfish.

Map showing the MPAs and MCZs around the Isle of Wight. Source: Natural England, via Southern IFCA

Map showing the MPAs and MCZs around the Isle of Wight. Source: Natural England, via Southern IFCA

These classifications are designed to prevent destructive activity – including overfishing – and protect biodiversity.

But enforcing borders on shifting sands isn’t easy, as any dog-owning Islander who has tried to stay on the right side of the groyne will tell you. Harder still at sea, as any parent who has tried to draw territorial boundaries in a bathtub will tell you.

Water flows. This has led to MPAs and MCZs being widely known as ‘paper parks’ – ineffective and ephemeral.

Policing this patchwork of protected waters lies with multiple agencies. The Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA) are responsible for the enforcement of fisheries legislation up to the inshore fishing boundary of six nautical miles. Meanwhile, the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) has overall responsibility for the protection of marine environments and administration of the byelaws which safeguard fish stocks, underwater ecosystems, and wildlife in the UK’s network of marine protected areas.

Garry Oates doesn’t hold much faith in either: “they’re all useless from my personal experience – it’s really frustrating to me.” He’s not the only one with such a dim view. Local fisherman of over 40 years Mike Curtis, of Captain Stan’s Bembridge Fish Store, says he sees international trawlers in forbidden areas “all the time”, sometimes specifically targeting seabass – a protected species and firm dietary favourite of cetaceans. Just recently, he says, he reported a foreign-registered vessel fishing off the South Coast of the Isle of Wight with its automatic identification system (AIS) off, providing video evidence to the MMO. “But they don’t enforce it at all,” Mike says. “They just don’t care.” The official response from the MMO is that they "adopt a risk-based approach" to the monitoring and enforcement measures at their disposal. Information on potential offending is evaluated in line with the National Intelligence Model – the same framework which informs the response to criminal investigations.

Waters around the Isle of Wight are also partly protected by the Royal Navy’s Overseas Patrol Squadron. On the FastCat ferry back to Ryde Harbour from my first trip to London in almost three years, I meet staff crew member Rod Cornwell. Before Wightlink, he worked fishing enforcement with the Navy from Portsmouth Harbour. Part of his job involved boarding ships and checking fishing quotas. I ask him – as I ask everyone, these days – about bycatch. “Oh yes,” he says. “The amount of wastage on those fishing vessels was absolutely indiscriminate – the things you saw.”

Rod Cornwell, Wightlink employee, used to do fishery patrols with the Royal Navy

Rod Cornwell, Wightlink employee, used to do fishery patrols with the Royal Navy

Curious to learn exactly how many, I submit a total of 20 Freedom of Information Requests to all UK police jurisdictions with a coastline. Bar a summer internship as a picture researcher, it is the most time I have ever spent copying and pasting: the pinnacle of investigative journalism dreams. As the results trickle in one by one, a pattern forms. Crimes against cetaceans are, it turns out, not ‘Home Office recordable’ – they have no official classification code. Still a crime, but too niche to warrant its own column on the grand master criminal spreadsheet. As such, there is no easy way of sorting through the data which I have asked for. Some help anyway, using a manual keyword search. Others deem it too laborious a task. Either way, the results are the same: the overwhelming majority of UK coastal police forces have no crimes recorded relating to cetaceans at all. Each has their own way of putting it: "no information stored", "zero records", "does not hold any information pertinent to the request." Cleveland – which has eight miles of unbroken beaches upon which cetaceans sometimes strand, one of which recently played host to a life-sized model of a sperm whale as part of an interactive piece of environmental theatre – hasn’t recorded any Wildlife Crime (cetacean or otherwise) at all since 2015. Nil points. Those that did report a small number of incidents – Devon & Cornwall, Norfolk, Northumbria, and North Wales – cited evidential difficulties, resulting in no suspect being identified.

PC Mark Webb is the Wildlife and Rural Crime officer for the whole of Hampshire Constabulary – covering the Isle of Wight but based in Bishops Waltham. For ten years before that, he was a marine unit officer. He can only recall four incidents of cetacean disturbance; all to the South of the Island, all by leisure powerboats. Over email, he tells me that the lack of statistical priority given to wildlife crime by the government means that they can be open to different interpretations by different forces. “It would be fair to say that crimes against cetaceans are rarely identified and reported,” he says. “Often we are never advised that a crime has occurred, let alone having enough evidence to identify an offender or proceed to prosecution.”

Still, there is some hope. Launched in 2021, Operation Seabird is a joint national effort between the MMO, wildlife groups including the British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDMLR) and RSPCA, and coastal constabularies to raise the profile of marine-based wildlife crime. PC Webb cites the recent successful prosecution by North Yorkshire Police of a cetacean-corralling speed boat owner.

For now,‘crimes against cetaceans’ continue to operate much like a fill-in-the-blank party game.

Until now, I had been thinking of the place where she lay as a crime scene. Maybe it was. Maybe it wasn't. Maybe she was just disorientated, as I am now.

After all, the Solent is far from silent. Its twin harbours are a constant hive of activity. Portsmouth, the UK’s second busiest cross-Channel port, has over 300 significant movements a day. It may not have the levels of military sonar said to have caused the mass strandings of dolphins across the Black Sea region, but active sonar is enabled (“when operationally necessary and for training purposes”) at various frequencies throughout the Royal Navy’s Portsmouth Harbour fleet: echo sounders for safe navigation, anti-submarine warfare, and mine clearance. Southampton too, as the UK’s ‘most productive’ container port, ‘number one’ vehicle handling port, and ‘Europe’s leading’ turnaround cruise port, produces a daily underwater symphony. During Cowes week, a cacophony. Its latest purpose-built deepwater quay saw a major dredging operation to 16 metres below low water to welcome the biggest ships in the world; carrying solar panels from Suez, air conditioning units from Antwerp, towers and tonnes from Tangiers.

It is the underwater equivalent of a school fair: high-pitched skipping rope squeals, feedback from the too-old sound system, a basketball ricocheting out of time. While we can grin and bear it, cetaceans cannot.

Sounds propagate in water, impeding their ability to communicate, navigate, hunt, feed, and reproduce. Blinded by sound.

As the slightest scrape inflames a hangover, noise pollution will further traumatise an already less-than-healthy cetacean.

Beyond noise, marine pollution is a major impairment to cetacean’s immune systems. Most often, we conceptualise this in Big Pictures: entanglement in the tail of a birthday balloon, golf-ball down the blowhole, the ingested DVD case that broke the sei whale’s back.

These are only the most visible examples.

Cetaceans are bioaccumulators. They feast not only on fish but on all the things we cannot see. Macro and micro marine plastics, yes, but also substances like the pesticide DDT and PCBs – highly carcinogenic chemical compounds once used ubiquitously in everything from cosmetics to clothing. Both banned for decades but still heavily present in marine environments. Many man-made pollutants (past and present) are lipophilic, meaning they are easily absorbed in the fat which constitutes between 15% and 55% of a cetacean’s body mass. Harbour porpoises like mine are particularly susceptible to the reproductive effects of toxic PCB accumulation, resulting in poor fertility in juvenile males and miscarriage in females. Calves that make it to term are born carrying a neurotoxic cocktail of chemicals which increases with each feed from its mother’s milk. Because of this, the toxicological analysis of blubber has been a historical focus of CSIP post-mortem investigations.

I am filter feeding now: accumulating cetacean-based knowledge at a rate of knots. At the same time, I am accumulating knowledge on a parallel course. In January 2022, prompted by a prolonged sense of powerlessness and regular waves of eco-guilt, I swap my job as the Editor of local lifestyle magazine ‘Style of Wight’ for Editor at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The cultural and content shock is real, but as I navigate the long-craved transition from crewnecks to climate change, brunch to biodiversity loss, and crushing consumerism to the circular economy, the bigger picture starts to sink in. A work-based crash course in ‘systems-thinking’ helps me to better understand the complexity of strandings.

I already know from Rob the Strandings Man that the idea of a single death is misleading. Death is no more definitive than life is linear. In cetaceans, each co-morbidity has a corresponding co-morbidity: one that is severely malnourished may have overlapping symptoms including infection of the central nervous system, viral load, or parasitic infestation.

With each individual immunological degradation, another (and another) becomes increasingly likely. Isolating these intertwined factors is like trying to separate grains of rainbow kinetic sand after they have been mixed.

Many scientists, academics, and practitioners – Rob Deaville included – describe cetaceans as a sentinel species for both ocean health and human health. Witnessing what is happening to them tells us both what is happening in our waters and what will happen to us.

A Canary in the Solent.

Though it looked less and less likely that I would ever get to the bottom of my porpoise’s death, I felt compelled to finish what I had started. If I didn’t try, I wasn’t sure anyone else would. One harbour porpoise on the Isle of Wight wasn’t going to raise alarm bells: it wasn’t a humpback whale in the Amazon rainforest, mass event on a remote New Zealand beach, or even a 12-metre-long marine giant in Clacton-on-Sea. A minor mort, not a Great Dying – yet.

My porpoise was the thirteenth cetacean to strand on the Isle of Wight in 2020. Nationally, the six hundred and fifteenth. Officially: SW2020615.

Records began in 1990.

Since then, the CSIP has recorded the deaths of eight thousand, six hundred and fifty-one harbour porpoises alone.

Comparatively, mine is a dot on the data, a drop in the ocean.

But there are others whose digital graves remain unmarked. Whether or not a stranding even makes it as far as a dot on a data-sheet is largely dependent on where it beaches and who finds it. In reality, not every animal washes up at a budding journalist’s feet.

By virtue of a 1324 statute enacted by King Edward II, all cetaceans (like swans) along the UK coast are technically owned by the Crown. This royal prerogative means that stranded cetaceans – being ‘Royal Fish’ – should, by law, be reported to the Receiver of the Wreck. However, when contacted, the Crown Estate’s ‘Transparency Manager’ told me that it had no records of any Isle of Wight cetacean strandings at all.

For most people, the Coastguard more immediately springs to mind. Jamie Woodford and Mike Riley are volunteer rescue officers from Ventnor, one of the Island’s three Coastguard Rescue Teams responding to a range of callouts across the Island’s South Coast: from casualty extractions to ordnance discoveries. and, from time to time, dead cetaceans.

Jamie Woodford and Mike Riley, Ventnor Coastguard

Jamie Woodford and Mike Riley, Ventnor Coastguard

Calls are triaged by the National Maritime Operations Centre in Fareham. Back on the Island, volunteers like Jamie and Mike are tasked with documenting its size, sex, and any distinguishing features. Their initial assessments are passed onto the CSIP who, if it is in a good enough condition, may decide to bring the body back to London for further investigation.

Less frequently, the average dead-cetacean-discoverer might take it upon themselves to call the RNLI, Police Maritime Unit, RSPCA, or British Divers Marine Life Rescue. It doesn't much matter which, for the majority of the many organisations that may, at one time or another, be contacted with a variation of “I’ve found a dead dolphin…” will end up reporting into the same pool of knowledge: the CSIP, who collate and contextualise the UK’s national dataset on cetacean strandings.

But for plenty of others – my husband included – the council is their first thought. Only unlike the myriad of marine organisations that sing roughly from the same hymn sheet, there is no legal requirement for local councils to do anything in particular with this information.

Prior to 2015, the Isle of Wight council didn’t keep any records related to cetacean carcasses at all.

Back at CSIP HQ in London, Rob is resigned to the reality that they won’t get to hear about every single animal. Some areas – such as Cornwall – have highly developed networks and excellent working relationships between councils and conservation groups. But reporting effort varies by region. “Unfortunately” he concedes “things will always fall through the net – no pun intended.”

Working at scale, Rob is right to be pragmatic: in the grand scheme of global strandings, the poor processes of one coastal council are hardly newsworthy. Though small, the lack of local surveillance troubles me.

On an emotional level, it feels not just like a gap in the data but a gap in environmental empathy.

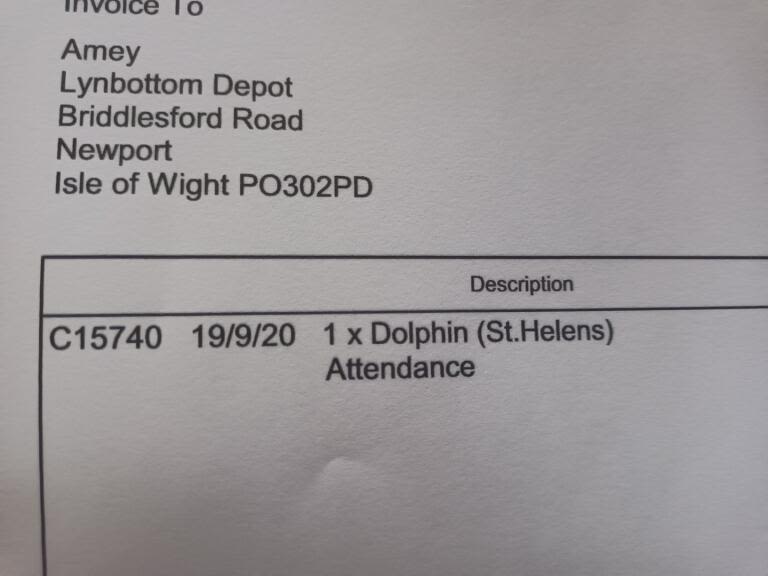

Though I have been assured my porpoise has been “appropriately dealt with”, I crave more. I want to know where she went – not in a spiritual sense, but literally.

Natasha Dix is Strategic Manager for the Environment at the Isle of Wight Council, responsible for "delivering strategic leadership for infrastructure PPP contracts, climate change strategy, waste resource management, coastal protection, and Biosphere support." Pinning her down for an interview has been tricky, and she is chaperoned online by a representative from the council's comms team.

I ask her to walk me through the physical process of what happens to cetacean carcasses after they have washed up on Island beaches. What follows is, in her own words, “a complexity.”

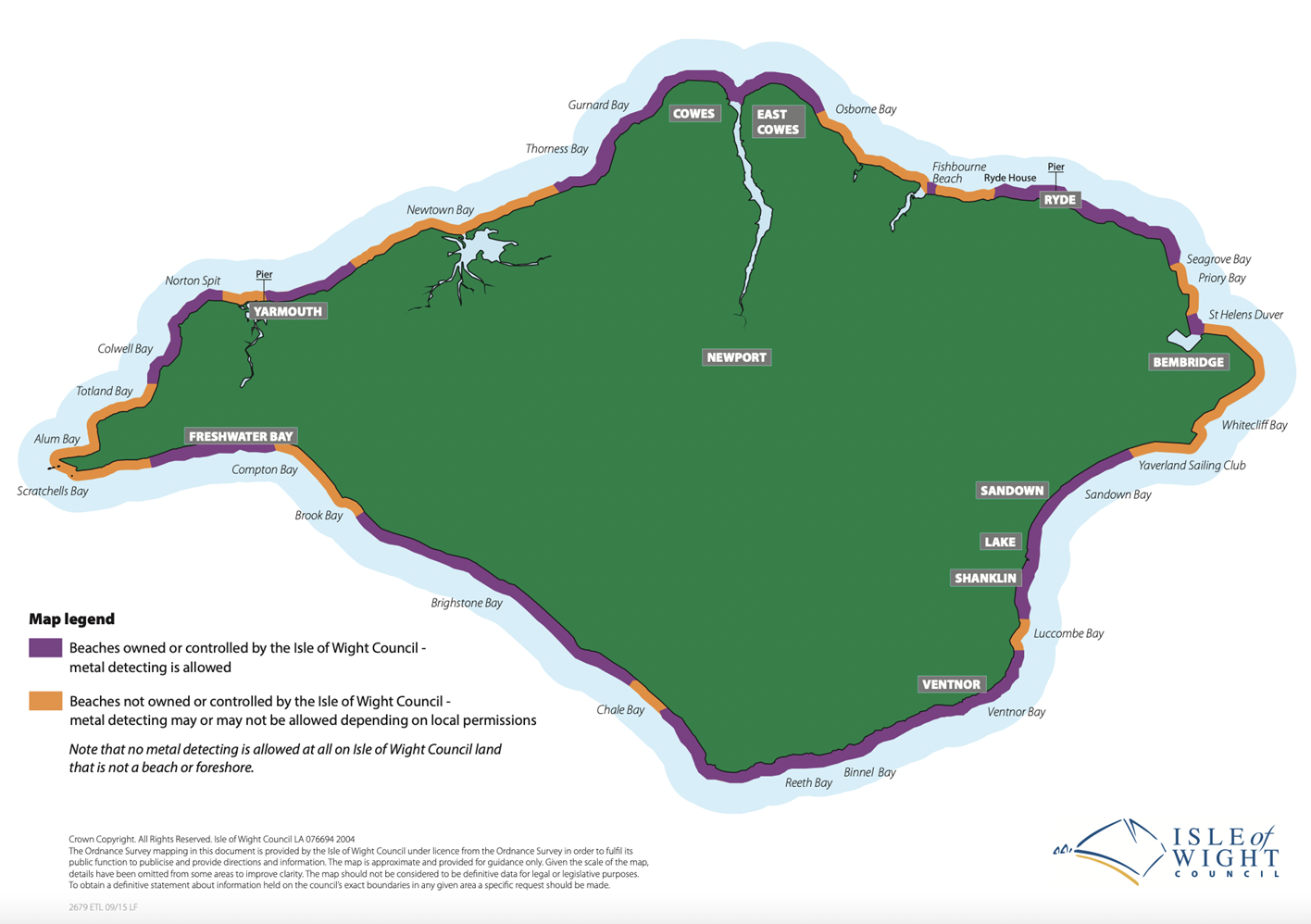

Simply, the responsibility for the safe removal of a cetacean carcass from a beach lies with the landowner. Most, but not all, of the Island’s most popular beaches – including Ryde, Ventnor, Shanklin, and Sandown – are owned by the Isle of Wight Council. Other stretches are council-controlled under lease from the Crown Estate. Some coastal areas, such as Newtown Harbour, Nodes Point at St. Helens, and Whitecliff Edge at Bembridge are owned by the National Trust. Queen Victoria’s private beach at Osborne House is managed by English Heritage. The rest, including Luccombe Bay, Compton to Brook, and parts of Fishbourne, are privately held by individual landowners. In practice, Natasha tells me, it is usually easier for the Council to deal with the carcass themselves than enter into a lengthy back and forth with whoever is technically responsible.

Map showing beaches owned or controlled by the Isle of Wight Council – reproduced with permission

Map showing beaches owned or controlled by the Isle of Wight Council – reproduced with permission

“We have a variety of contractors who do different things depending on where the animal is found” she tells me. If it is on a beach, the carcass is most likely to be collected by workers from Amey, the council’s waste services partner. The bagged body will then be delivered to Barry Isaacson, whose two Island businesses – Jervis Court Equine and The Lodge Crematorium – specialise in the disposal of everything from cows and cats to horses and hamsters. Occasionally he is asked to collect the carcass himself. Over on the other side of the Island local grounds maintenance company Brighstone Landscaping is similarly contracted – although they tell me they have not collected anything since 2019. These wilder West Wight remains (where the beaches are more remote and less accessible) are taken not to Barry Isaacson but to Guy Adkins, at a site formerly known as A&D Biles at Somerton Farm in Cowes. Associated with this working arable and livestock farm that was not so long ago the Island’s largest ‘knacker yard’ is a holiday cottage marketed as a ‘perfect rural retreat’.

Not all stranded cetaceans are collected from the beach. In the (admittedly less common, but nevertheless occasional) case of a whale on a walkway, a dolphin on a drive, or a porpoise on a pavement, the animal is automatically considered, in the eyes of the Isle of Wight council, as roadkill.

An Island Roads waste wagon on Shanklin Seafront

An Island Roads waste wagon on Shanklin Seafront

As such, it is dealt with in the same way as a dead fox, badger, or squirrel. The contract for the disposal of dead animals from the Isle of Wight highway network lies with Island Roads who, in turn, send these animal carcasses to Mr Adkins at Somerton Farm in Cowes. Though I have been unable to personally verify their claims, I am told by three separate sources – including two Island Roads employees who do not wish to be named – that these animals are stored in a "disgusting" outdoor, unrefrigerated and unsealed wheelie bin down a publicly accessible farm track.

When contacted for a response prior to publication of this article, Island Roads says that it “carries out its duty to remove and dispose of carcasses found on the highway network sensitively and in accordance with all guidelines and regulations.” At the Somerton site, I am told that carcasses are placed in an airtight bag and taken to a locked container away from the public road network. This initial unit is not refrigerated. However, I am told that carcasses are transferred daily to a second sealed and refrigerated container. I ask to visit the site to see for myself, but receive no response.

Natasha Dix has not heard of A&D Biles or Mr Adkins – or of Somerton Farm. “That’s not someone we use in our waste contracts.” After a pause, involuntary eyebrow raise, and pencil quiver from me, she clarifies. “Our service providers are given a specification which they are procured to work under. Part of that specification is to collect dead animals from Council owned and managed land. But it’s up to them to deal with the onward contract. Once they’ve collected an item of waste – which includes dead animals – it becomes their property for them to dispose of.”

Once removed from Island beaches, she says, all carcasses are incinerated on-site at The Lodge Crematorium in rural Rookley. Except they are not. I already know from speaking with Barry Isaacson that dead cetaceans are transported in a van along with a twice-weekly shipment of fallen farm stock including cows, sheep, pigs, and horses via ferry to Farm Equine (formerly J.H. Watson & Sons) – another family-owned ‘Jervis Court Farms’ business in Swanmore, Southampton.

It is Natasha’s turn to raise a remote eyebrow.

“That’s news to me,” she says.

As for the occasional dead dolphin that, like a rabbit-in-the-headlights, finds its penultimate resting place somewhere other than the beach? According to Guy Adkins of Somerton Farm, “anything he is given” is taken to Harry Hawkins & Partners – a mainland incineration service in Horsham, providing disposal of livestock across the South Coast. Here, Joan Hawkins confirms that Mr Adkins is a "regular", bringing mixed bags of roadkill and assorted animals several times a month for mass incineration. What remains is transported to Waddingtons, one of the UK’s largest animal by-product processing plants, to be rendered into biofuels, pharmaceuticals, or pet food.

I was warned it was a complexity.

I cannot work out what I am dealing with: a classic case of supply chain sight loss or something more sinister? Contacted for comment, an Isle of Wight Council representative says Natasha Dix – despite leading the Island's waste infrastructure and resource management strategies – is "not expected to have personal knowledge of individual waste disposal routes."

I am not naive enough to imagine that finances don’t come into it somewhere. Sue Hemmings runs Pets at Rest, the other crematorium service for domestic animals on the Isle of Wight. Unlike Barry, she hasn’t had a cetacean come through her doors for years – not since she raised her prices to reflect the fact that each animal is cremated individually “I don’t care whether it’s a pet dog or a dead dolphin – they all deserve the same compassion” she says.

Throughout our interview, Natasha Dix has alternately described my dead porpoise as a ‘product’, ‘waste’, and ‘remains’. Save for an inflatable pool ride-on I remember from childhood I have never been overly drawn to creatures of the sea the way that some are. Nevertheless, the thought of my porpoise bagged, binned, and burned without a second thought is threatening to turn me into a mad dolphin lady before I hit 35.

I put this notion of wildlife as waste to Captain Garry Oates. “We believe there should be a dignified response. When sentient mammals like dolphins and porpoises die, it’s an emotional thing. Instead, they are abandoned by different authorities who all pass the buck. They deserve respect; not just be put in a lorry and crushed up.”

Such severance from the natural world is seen across the globe. Scientists have been warning for decades that the destruction of habitat and direct interactions with wildlife risk unleashing emerging pathogens.

Though it is but a diamond-shaped speck on the world stage, what happens on the Island won't necessarily always stay on the Island. It seems inconceivable that the next global pandemic could one day be traced back to a British beach – but not an impossibility.

Keen to get an outsider’s take, I speak with Andrew Knight, Veterinary Professor of Animal Welfare and Ethics at the University of Winchester. “We know that the majority of new and emerging human diseases come from animal populations, so I would be concerned for the welfare of people handling and transporting those carcasses if they haven’t had specific biosecurity training to protect themselves and anyone else they come into contact with.”

Stephan Voight – the Island’s former Area Coordinator for the BDMLR – explains further the risks of close contact. “One has to be very careful. If you lift an animal, bodily fluid could still come out – you don’t know what bacteria, viruses, or parasitic load it might harbour. Sadly, though, people tend to ignore the risk of diseases they can’t see until they’re confronted with the consequences – it’s the same with Covid.”

I ask Natasha Dix about worker protection. She assures me that “all collection staff have full PPE for hazardous situations, including going out to collect dead animals.”

My porpoise was left on the beach at St. Helens for 48 hours before being collected.

Invoice from Barry Issacson at The Lodge Crematorium to Amey Waste Services for the removal and disposal of my dead porpoise in September 2020

Invoice from Barry Issacson at The Lodge Crematorium to Amey Waste Services for the removal and disposal of my dead porpoise in September 2020

Others wait even longer. With each hour that passes, the risk to public health increases. The fluids and tissues of any animal – cetaceans included – are a potential source of zoonoses.

Though Covid has done much to increase awareness, there is a tendency to associate zoonotic disease with mosquito-borne fevers, plague-carrying rats, and wet-market bats rather than dead dolphins on a cross-Solent ferry.

Red Funnel, who run the Cowes to Southampton route, accepts that shipments containing Category D Hazardous Waste –including clinical waste, persistent organic pollutants, and cetacean carcasses – do take place. They tell me that these shipments are stowed separately and adhere to strict health and safety regulations guidance as per the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code. Drivers are, however, required to vacate their vehicles as soon as they are parked like everyone else. There are no restrictions, a Red Funnel spokesperson confirms, preventing them from grabbing breakfast from the busy customer cafes or using the onboard facilities.

Fallen farm stock, assorted roadkill, and stranded cetaceans are transported across the Solent for mainland incineration. Image credit: Red Funnel Group

Fallen farm stock, assorted roadkill, and stranded cetaceans are transported across the Solent for mainland incineration. Image credit: Red Funnel Group

This, says Professor Andrew Knight, is somewhat concerning. “It is an obvious biosecurity hazard when carcasses that are potentially pathogenic are being transported on public transport.”

Handling deceased cetaceans carries significant health risks.

So does rescuing live ones.

The British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDMLR) are a national charity with a network of regional marine mammal medics who respond to live cetacean strandings across the UK. On the Isle of Wight, there are currently 9 or 10 active volunteer members, headed up by current Area Coordinator Naomi White, a veterinary assistant and mother of three.

Contrary to the organisation’s name, you don’t have to be a diver – or even a strong swimmer – to be a marine mammal medic. But you do have to be strong: dolphins can weigh between 150 and 200 kilos. They are actively recruiting, Naomi tells me with a hint of a hint. I am tempted – were it not for the fact that three of them have herniated discs and, after carrying two big babies, my core strength is not what it used to be.

I join Naomi and her band of marine rescuers at one of their training refresh sessions, held a few times a year. It is the first – but not the last – hot day of 2022; the kind that makes the beach car park smell like sunscreen, slushies, and public toilets.

In a couple of days, the Island will be in full-on Festival mode. Traffic is already starting to pick up as tens of thousands make their way over for the four-day weekend. Appropriately for me and my burgeoning beat, this year’s theme is ‘Sirens & Sailors: The Life Aquatic’ – revellers are encouraged to dress up as mythical creatures from the deep, turning the 180-acre site into a ‘marine paradise.’ Consequently, we are each a bit late.

A raft of specialist equipment is unloaded from Naomi’s van: a pontoon for refloating; a kit bag containing everything from surgical gloves and KY Jelly to face masks and flags; and a compressed air canister. Were it not for the fact that they have changed into heavy-duty dry suits – rescues can last for hours and wetsuits just aren’t warm enough – it would look as though we were going camping. We make our way down the slipway and onto Yaverland’s wide sandy beach. I carry a bucket.

The BDMLR works closely with the RNLI, Coastguard, Police and Fire Brigade to ensure public safety. Ahead of this planned training exercise, they have informed the Coastguard to prevent unnecessary callouts from well-meaning passers-by.

The volunteer medics are trained in marine mammal biology, first-aid, and rescue techniques. I am here for the speeded-up version. It strikes me as a suddenly amusing parallel that today is the day of my eight-year-old son’s first PSHE lesson, and here I am on Yaverland beach learning how to identify the genitalia of an inflatable dolphin (this one is female). Ordinarily, she would be filled with water for more realistic handling, but there is a puncture and replacements are expensive so she is held together by gaffer tape.

A thorough physical examination is undertaken using a body scoring system. Nutritional condition is assessed by weight and thickness of blubber. A list is checked: is the dorsal fin concave, does its nuchal crest look depressed, is the blowhole functional? Its temperature is taken and its heart rate is monitored. Marine mammal medic Nigel Dove carefully wraps it in a single wetted sheet with a ripped hole for the fin.

Unless it scores highly and is deemed to be in good health, refloating – a carefully planned procedure which would normally require at least four people on each side – is deemed too risky. Chances are the cetacean will simply repeatedly restrand. I recall a once-viral video showing beachgoers in Brazil dragging a pod of 30 stranded dolphins back out to sea. “Yes, and the thing is most of those dolphins would have died from drowning” Nigel says, explaining that when a cetacean becomes stressed or confused the sphincter muscle that controls the automatic opening and closing of the blowhole can become lethargic.

Everyone has a part to play. Someone is a beach master, to guard valuables while the team works. Someone else is assigned to crowd control, in charge of protecting the public and the cetacean from mutual harm. Today, that person is Naomi. As the foot pump slowly animates the dolphin into being, a solitary surfer in board shorts approaches. “Here we go,” says Naomi. Soon after, two children run up with a large dog. “Is that a shark?” they ask, excitedly. “It’s a dolphin, but it’s not real,” Naomi calls back. Devastating disappointment: “Awwww.”

The person with the most reassuring voice – normally a female – stays up by the dolphin’s head, saying soothing things and helping to keep it calm. Since most viruses and pathogens are emitted via the blowhole, this is the job with the highest level of zoonotic risk requiring the medic to be double-masked and gloved.

Sadly, I learn that survival is the exception, not the rule. In most cases, the cetaceans that live strand on the Island are found to be suffering from a multitude of illnesses, and it is often kinder to euthanize them. Seeing my disappointment, Naomi promises to call me the second they get a call out. For weeks I hold onto this hope, imagining playing my part in a successful rescue operation and manifesting thoughts of a happy ending swimming off into the East Wight sunset.

Months pass. Naomi and I check in every now and then, but nothing.

Nothing alive, at least. One strands and strands again. Local news outlet Island Echo report the discovery of a dead dolphin on Players Beach in Binstead. The hero image is far more gruesome than mine; charred and swollen, the colour of rusty nails.

Dead dolphin on Player's Beach, Binstead, June 2022. Photo credit: Leah Southam

Dead dolphin on Player's Beach, Binstead, June 2022. Photo credit: Leah Southam

Several of the comments underneath indicate that it had been floating around for a while: one had reported it two days previously, another a week before that. Someone else claimed it had landed on the beach near Ryde Pier Head – three miles away, three weeks ago. Local resident Leah Southam tells me that she called the council, who told her “it wasn’t their problem.” Island Roads said – since the beach was a privately owned one – much the same. Someone else called The Coastguard, who took measurements for the CSIP (at least). Another rang the Bembridge RNLI, who rang the council waste team, who "weren't interested."

By Saturday 25th June it had washed back out to sea on a high tide. Its smell remained: “like foul rotten meat, with the hint of something else that turned my stomach” Leah remembers.

Badly decomposed and rotting. Photo credit: Leah Southam

Badly decomposed and rotting. Photo credit: Leah Southam

Dogs rolled in the residue, carrying particles home on their paws.

On sand, shingle, and my desktop spreadsheet, the bodies pile high. I have become so hyper-focused on the details of cetacean death that I have no real concept of what a cetacean life actually looks like.

I know they exist because they keep washing up. Every now and again a video emerges on local social media: pods of twenty or more play around paddleboarders; a sailing boat surrounded at St. Helens; tourists thrilled by sightings off The Needles. Though I know from the BDMLR not to encourage these interactions, I can’t help but feel a little jealous: why did my experience have to be one of decomposition?

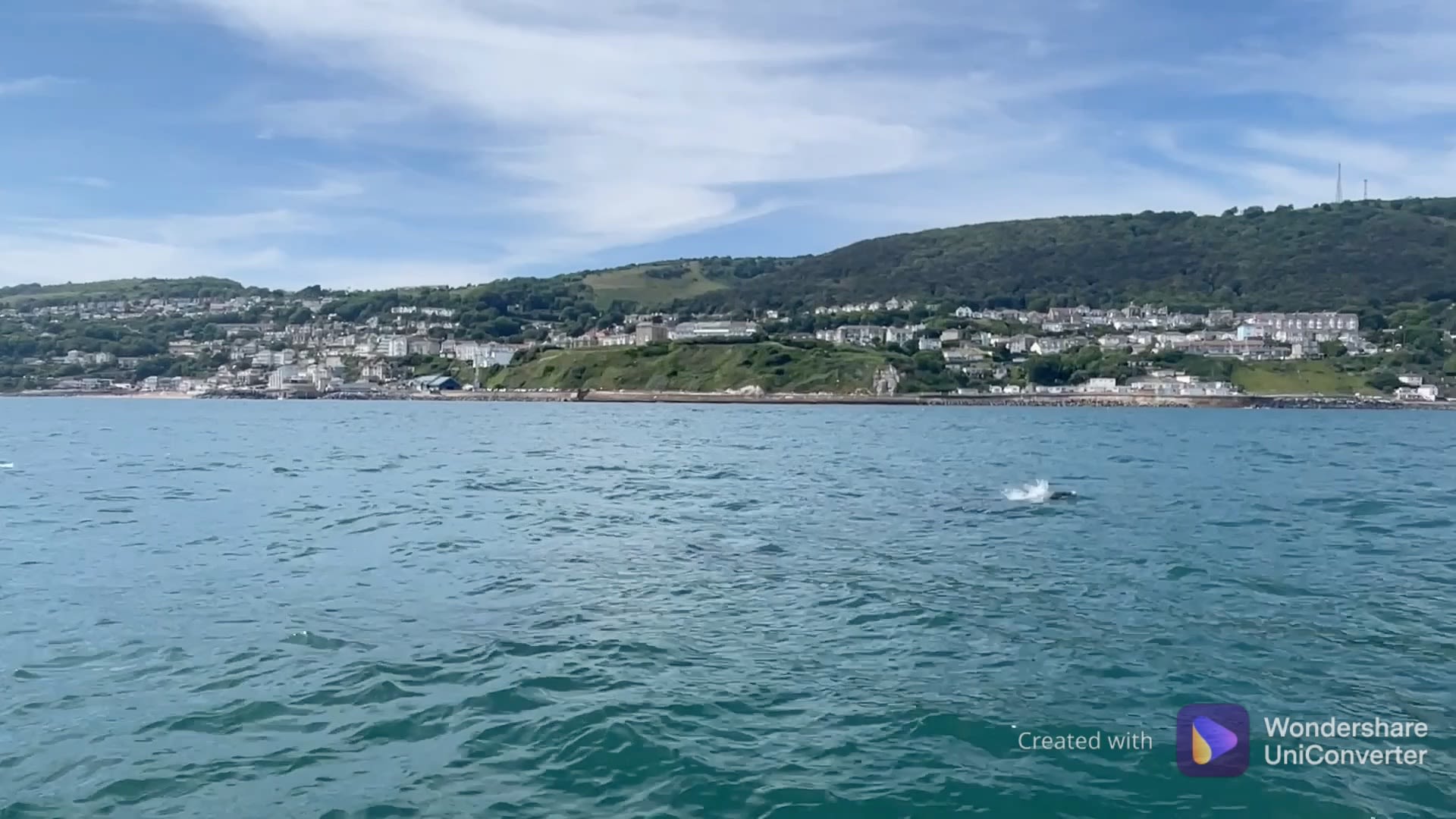

One of those videos belongs to Ventnor fisherman Ed Blake, racking up thousands of views. I make contact. Ostensibly, because I’m lacking the kind of local perspective to help me better understand the Island's waters. But, if I’m being truly honest, I’m also hoping that we’ll see some dolphins.

This is not the kind of fishing so dramatically implicated in the global death of cetaceans. Small-scale fisheries like Ventnor Haven rely on the health of local fish stocks and marine ecosystems to guarantee future yields and therefore have a vested interest in their protection.

23-year-old Ventnor Pride II, moored inside the Haven

23-year-old Ventnor Pride II, moored inside the Haven

On arrival, my journalistic integrity is tested when Ed asks me if I want him to put his yellows on for the photo. I consider, then concur; as swayed by the Romance of the Sea as I’m sure many a tourist (Mary Berry included) were before me.

Despite its old-fashioned appeal, bycatch is always a possibility. When Ed was three, a 20-foot minke whale became tangled in one of his father’s lobster pots, and he was subsequently hailed in the local and national press as the country’s youngest ever fisherman with the largest ever catch.

Three-year-old Ed Blake landing a 20 ft whale: Isle of Wight County Press, August 1997

Three-year-old Ed Blake landing a 20 ft whale: Isle of Wight County Press, August 1997

Generally, accidental bycatch on this kind of vessel is on a more benign scale: like the single conger eel that I nearly tread on as I climb aboard Ventnor Pride II.

Ed Blake's family have been fishing these waters for decades, although his dad is the first full-time fisherman since the 1800s. “Up until the 1960s there was more money to be made in renting out deckchairs on the beach”, he explains, referring to the extended family business Blakes Longshoremen.

He tells me that sightings of cetaceans have increased noticeably. “Five or six years ago we would see dolphins very infrequently inshore. It used to be once or twice a year; now it’s once or twice a week.” Surprisingly, considering their notorious shyness, “the main increase we’ve seen is in porpoises. At times we see them every day. But it’s almost impossible to get camera footage of them because they don’t seem to follow a pattern like dolphins – by the time you turn your camera round they’re gone.”

As the 23-year-old boat chugs into action, I attempt a subtle stabilisation and brace against the really relatively calm waters. This is the daily grind for Ed; the sea is his second home. “As kids”, he says as he manoeuvres out of the Haven, “we weren’t allowed to cross the road, but we were allowed to row down to Woody Bay.” Island Life, as they say.

Ventnor fisherman Ed Blake

Ventnor fisherman Ed Blake

As is often the case in conversations about climate change, plastic pollution acts as the ice-breaker to other things. He tells me of balloons mistaken for buoys and a lego door wrapped around a dogfish’s head.

It is the Summer Solstice. The boat rounds the corner towards Luccombe and I realise that we are directly below the coastal road that a year ago was my commute to work. From here, you can just about make out the bend at which the car radio would crackle-switch from Isle of Wight Radio to French station NRJ à Cherbourg. Further along, Ed points out a landslip; this side of the Island, from here and back to Ventnor, Bonchurch. St. Lawrence, Niton, and Blackgang is known as the Undercliff, the largest urban landslide complex in North-West Europe. “It was really hot, that first lockdown, and it just cracked – the land just came away. It took a long time to clear, we couldn’t net around here at all because there was just so much debris.”

On land and at sea, stability is shifting at speed. “We always used to get tonnes of kelp” Ed tells me. “It’d be 10 foot long and get to the point where you literally couldn’t cut through it. But now we just don’t get it – only this mayweed stuff which grows like mad.” Although there are parts of the Island where kelp – essential for tackling the effects of climate change due to its ability to draw down and sequester atmospheric carbon – is thriving, on a national scale it is in retreat; pushed out by invasive alien species brought over on the bottom of container ships and cruise liners.

It’s not just the plant life that’s changing in volume and distribution. Ed reels off more proof points: mackerel that is coming earlier and earlier; crabs that are sticking around for longer; lobster larvae struggling to make it to adulthood; a superabundance of squid.

All are symptomatic of warming seas.

“Since 2016 the water has been getting warmer and warmer, to the point that we haven’t seen a cod for three years. In 2020 the water temperature hit 25 or 26 degrees in Sandown Bay – the Caribbean is 27. That’s bloody warm.”

Cold water cod and pollack have, he says, been replaced by volumes of warm-water silver shoaling fish: bass, bream, and mullet are loved by dolphins and porpoises alike.

Suddenly, as if summoned, there they were.

The boat slows and Ed shuts down the engine. He gestures up ahead to where, if I squint, I can see a splash in the sparkle. They see us, and the next thing I know there are dolphins on either side of the boat. All is silent as I regain my balance, reach for my phone, and watch.

We are as close to the sun as we’ll be all year and I am as close to dolphins as I have ever been. It is a precise planetary moment. My next thought is less poetic: they are huge. I am not completely unaccustomed to large animals – our family dog is a Great Dane. Nevertheless, these dolphins were truly, mind-blowingly, massive. Perhaps I had been using my dead porpoise as a reference point, which I had judged at the time to be roughly Red Setter sized. In any case, these cetaceans were more like cows jumping over the waves. They are dipping and diving and doing all the things you might imagine a pod of dolphins to do, only somehow more magical and more meaningful in real-time than in any video.

After my boat trip, I am adrift and agog. Seeing them ‘IRL’ has elevated the concept of my dead porpoise from corpse to corporeal. She was here. In an attempt to regain creative focus, I take the kids on a spur-of-the-weekend camping trip. Hardly a writer’s retreat, but a change of scenery at least. We stay in a tipi, tucked away in the private nursery area behind Ventnor Botanic Gardens. Since I left the magazine, I haven’t been to Ventnor in six months – now I am back for the second time in a week.

The site is surrounded by subtropical plants that thrive outdoors and unprotected thanks to the Mediterranean-like microclimate of the Ventnor Undercliff: huge spiky agaves, giant echiums, palm trees, and Australian eucalyptus. Unpacking our blow-up mattress while they chase each other round the tent, I notice two curious eyes watching me as I struggle with the foot pump. A gecko. Growing up on a compound in the semi-desert suburbs of Saudi Arabia, I am not shocked. They are as familiar sight in Ventnor as they were in my own childhood. Following the controversial reintroduction of chemical weedkiller Glyphosate by Island Roads in 2021 – a decision defended by the Isle of Wight Council – residents successfully launched a campaign to temporarily halt its use. One small win for locals and lizards.

The creature gives me one last look and runs up the central pole, but not before I have snapped a blurry photo to show the boys. They are disappointed to have missed it, so I suggest we give him a name. For reasons unknown, they settle on Bodhi.

That evening, as they watch Peppa Pig in bed and I return to the tangled tale that is starting to take shape in my head, I decide that my porpoise, too, deserves a name. “Oink oink” says the iPad. That settles it then – A Porpoise Named Peppa.

My choice is validated the next day by remote acoustics analyst Theo Vickers. A recent marine biology graduate, Theo spends his working days trawling hours of underwater sound data to distinguish between whale and submarine. He shares my intense interest in cetacean strandings and has been mapping them since he was fourteen. “I was a bit of a strange teenager” he says, by way of explanation.

Theo Vickers leads the way to Woody Bay

Theo Vickers leads the way to Woody Bay

As we walk – and talk – past fields of roan and white cattle and onto the wooden steps down towards Woody Bay, I relay the previous evening’s naming ceremony. “Etymologically, porpoise literally means 'pig-fish' – probably because it makes this little pig-like puff at the surface of the water” he explains. I squeal with anthropomorphic excitement at the aptness of it. “Perfect!” he says.

Picking a comfortable-looking rock to perch on, I give him the potted history of my discoveries so far. I am very relieved that he doesn’t look at me like I’m crazy when I mention that I first thought of my porpoise as a murder victim. “I mean, there definitely has been that misuse of cetaceans – Sea Shepherd documented evidence that some commercial trawlers even use dolphins as bait. In some cultures, fishermen must mutilate dolphins as part of an initiation ritual and bleed them out to attract sharks for sport fishing.”

"It's the unpredictability of everything" says marine expert Theo Vickers on the effects of climate change on local seas

"It's the unpredictability of everything" says marine expert Theo Vickers on the effects of climate change on local seas

He is particularly interested in the changes in fishing stock observed by the local fishermen at Ventnor Haven: “That’s a pretty good sign that the seas are warming up” he says. I show Theo my video, and he confirms that they are classic Bottlenose dolphins (like Flipper), part of a bigger ‘super-pod’ population that is primarily focused in South-West England. These sightings are becoming more and more common in our waters, he says, because “their prey is becoming less predictable, and so groups are having to search bigger distances to find food.”

I ask Theo what he thinks are the main impacts of climate change on the Island. “I think it’s the unpredictability of everything,” he says.

“The appearance of new climate change indicator species, the loss of previously abundant ones – these are all signs of an increasingly chaotic marine environment in terms of temperature.”

Ocean acidification, too, which will directly impact cetacean health, is likely to already be taking place in the English Channel. “It will affect different parts of the ocean disproportionately, but generally speaking high latitude temperate to polar waters are predicted to experience the biggest PH changes over time. That absolutely includes the Solent.”

Alongside his job, Theo is an underwater photographer and runs guided family-friendly fossil hunting experiences. When I get to the part about zoonotic risk, his eyes alight with the tell-tale look of someone who has, well, a tale to tell. “We had a dead porpoise at Atherfield. I thought ‘I’ll show the kids in this family, that’s quite an interesting thing that you don’t see very often – especially if you’re from London.’ I was talking to the parents and I turned around and the kids had put their hands in the putrefied organs in the body cavity. It was horrific. Really they should have had professional decontamination afterwards – imagine all the pathogens. Honestly, it was beyond belief, absolutely beyond belief.”

I pray that neither of my two would do that. But still, kids will be kids, and the gruesome anecdote serves as a further reminder of the importance of swift and effective public health measures.

Eighteen months after our first meeting on St. Helens beach, I visit Garry Oates at home in Sandown. I get a bit lost walking up and down side streets and call for directions. He beckons me back towards the council-owned car park where a car boot sale is being set up and welcomes me in through a side gate to a courtyard: Blue Seas Protection HQ.

'Captain' Garry Oates, at home – and Blue Seas Protection HQ – in Sandown

'Captain' Garry Oates, at home – and Blue Seas Protection HQ – in Sandown

In the backyard is an array of land-based vehicles which nod to their owner’s ocean-based enthusiasms: an old special forces vehicle converted into a campaign float “Fighting Crimes in Our Oceans”; an inflatable whale chained to a stationary hull; a vintage caravan, seaglass mobile swaying from its antenna; classic car propped up on shipping pallets.

Time has not dulled his passion. “We are fighting a war of marine conservation,” Garry says, leaning on the truck. “And it is a war – because everyone wants to take and destroy from the oceans.”

Inside, it is exactly the kind of cottage you would expect an ocean activist to live in: life rings hang from whitewashed walls; an oyster-pale ceramic dolphin sits atop an 18th century organ; dry seaweed drapes down the mask of Amphitrite.

I remark on the ceramic and Garry tells me that the manager of Sandown’s ‘Friends of the Animals’ charity shop puts cetacean-related bric-a-brac to one side for him.

If I’m not careful, I think, that’s exactly where I’m headed.

Garry introduces me to his partner, Sue Betts. We retire to the conservatory, where the specimens in jars – razor clams, shark cases, bladderwrack, and whelk egg clouds – remind me of a Potteresque potions store.

Files and folders are brought out, containing press cuttings, correspondence, and campaign documents. Their work to protect the sea and its inhabitants is tireless – and feels, I get the impression, at times fruitless. Frustrations are aired and aired again: about the lack of government action, the antipathy of authority. We sit in a conservatory on the Isle of Wight and lament the loss of marine life the world over.

Inside the Blue Seas Protection 'Shark Lab'

Inside the Blue Seas Protection 'Shark Lab'

Over a second coffee, I learn that Sue, who grew up in New Zealand, is from a long line of European whalers; Garry from a family of marine salvagers. I wonder if, on some level, these dual histories in ocean extraction have driven their life of environmental activism. As my eyes trace the contents of the glass containers, it occurs to me that my own childhood proximity to Middle Eastern oil and gas may have similarly prompted the path that I am now on.

Blue Seas Protection campaign for an end to destructive trawling

Blue Seas Protection campaign for an end to destructive trawling

I break from my thoughts and thank them for their time. “Thank you, Emma – for fighting for our oceans,” he says, showing me back into the Sandown sun.

During those first few weeks, before school and nursery are officially ‘out’, I finally have the headspace to revisit the stories of those I have met and spoken to along the way.

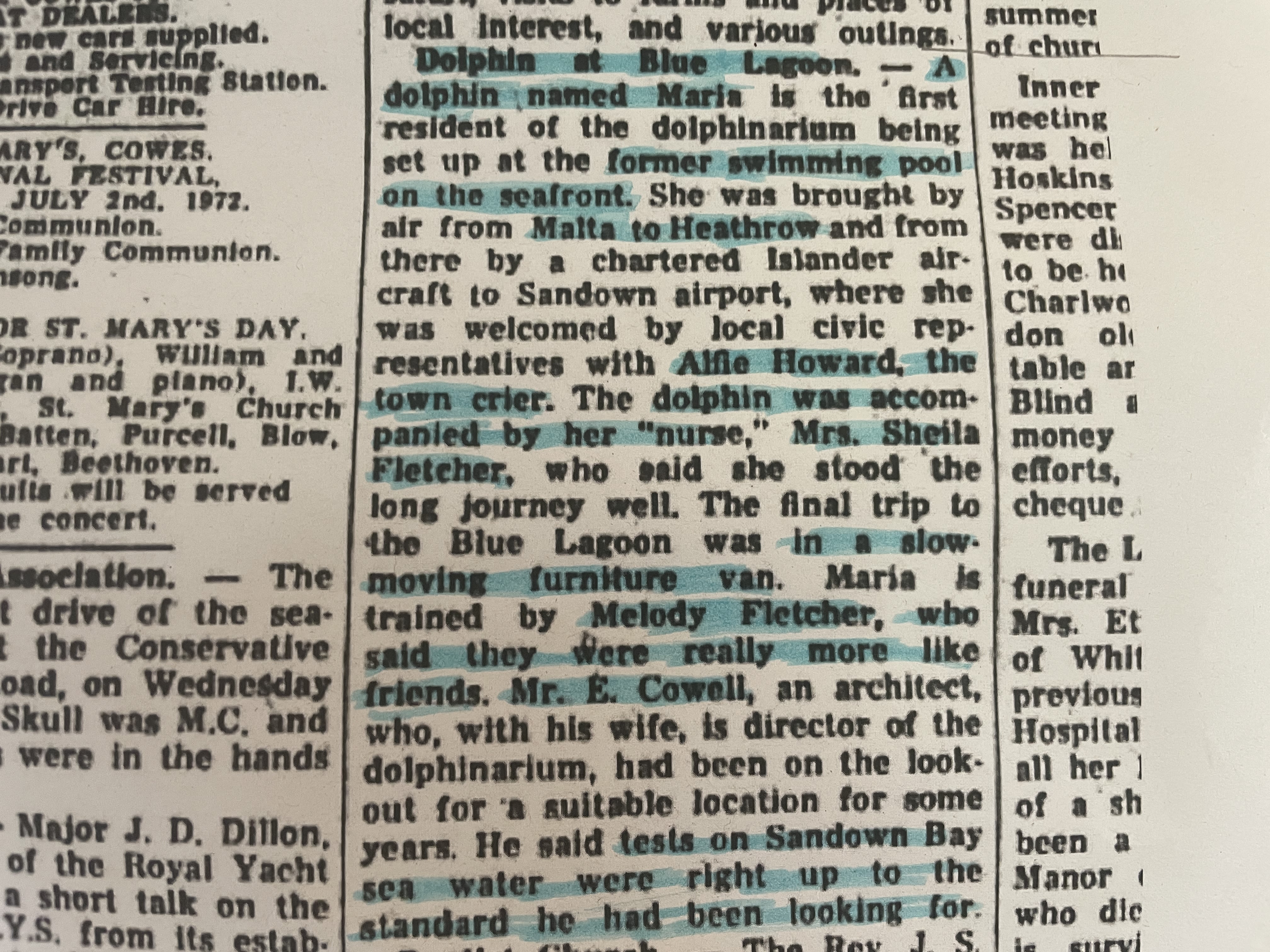

I remember Nigel Dove, the volunteer marine mammal medic, telling me about the time he helped load half a fin whale stranded on a sandbank between Seagrove Bay and Bembridge – with visible wounds from a ship’s propellor – onto a truck bound for Lynbottom rubbish tip. My cousin in Ireland shares memories of Fungie, the much-loved Dingle Dolphin who went missing in October 2020 – now presumed dead. I speak to a lady in Totland who once swam with a solitary (and sexually aggressive) dolphin called Georges at Compton Bay and another who remembers Daisy the Dolphin at St. Helens. Somebody tells me they remember there being a dolphinarium in Sandown in the 1970s, set in a disused lido, prompting a diversionary afternoon spent at the Isle of Wight records office peeling through press cuttings now blue tacked to my living room door.

A Dolphin Named Maria: Isle of Wight County Press, July 1972

A Dolphin Named Maria: Isle of Wight County Press, July 1972

Theo Vickers was the “little boy that read books about sharks” and Ed Blake the child who “had every single model of every single dolphin out there.”

Who knows what my boys will make of the summer that their mum was obsessed with a porpoise named Peppa.

I am attuned to their frequency now.

I notice one beached and bloated on a recreation ground after the annual Isle of Wight Mardi Gras parade. This year's theme is #ourfutureourworld; the papier mache marine giant suffocates under a cellophane blowhole. Another is spotted just metres from my original discovery – a discarded floatation device on a Sunday beach stomp.

I see them etched into the side of a beach hut; stamped on the bag of artwork my youngest brings home from his final day of nursery and floating inside the Turkish tourist snow globe my eldest buys me from a charity shop.

They are imprinted on the side of an inflatable sea slide, carved into a topiary hedge on the way to meet a new baby niece, and hidden in the pages of a bedtime Where’s Wally.

A Humpback is suspended from the treetops of Blackgang Chine, the oldest amusement park in the UK. I notice Dolphin fish and chip shops, care homes, cottages, and canine squeaky toys.

Like cetaceans, I sleep half-awake at the surface. In my dreams, Fungie is found.

Some days I feel weighed under by it all; a mermaid carrying a dolphin on its back.

For two years I have waded through the Island's waters in search of answers. Yet each investigative turn raises only weeds, exposing underwater tributaries beneath what I had once thought the sea floor. The current that has carried me onwards must surely slow soon. I crave conclusion.

On the 17th September 2022 I go looking for seaglass in an attempt to find closure in the complexity.

As the country mourns a monarch, I mourn a mammal – one of her own, a Royal Fish. Just as details of Queen Elizabeth II's official cause of death will remain private, the specific circumstances around how Peppa the Porpoise came to wash up at my feet on St. Helens beach two years ago will never be known. She may have become entangled, and then confused, and then sick. It may have been the other way around. Her home may have slowly become a place she no longer recognised – too noisy, too polluted, too warm. Each possible cause of death can be directly or indirectly traced back to us. Our ancestral anthropogenic actions.

Telling her story is both a rallying call to change and a simple act of remembrance.

This piece of hyperlocal 'climate and community' journalism was originally submitted as part of my MA Journalism Final Major Project at Falmouth University.

With thanks to the following for their advice, support, comment and contributions:

Ed Blake, Ventnor Haven Fishery; Sandy Chamberlain, Citizens Advice UK (also: mum and childcare provider); Kit Chapman, Course Leader MA Journalism, Falmouth University; Madeleine Cuff, Environment correspondent, The i Paper; Rob Deaville, Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme; Kate De Pury, EBU Moscow; Ahmed Elobeid, Met Police (also: husband and sage sounding board); Professor Andrew Knight, University of Winchester; The London Writers’ Salon Community; Robin McInnes, Coastal Geologist; Wyl Menmuir, Writer in Residence, Falmouth University; Jane Nash and Dan Milne, Narrativ London; Garry Oates and Susan Betts, Blue Seas Protection; Jane Qiu, Science Journalist; Tansy Robertson-Fall, Senior Editor, Ellen MacArthur Foundation; Emily Stroud, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust; Anita Varma, School of Journalism and Media, University of Texas; Theo Vickers, British Antarctic Survey; Naomi White, British Divers Marine Life Rescue