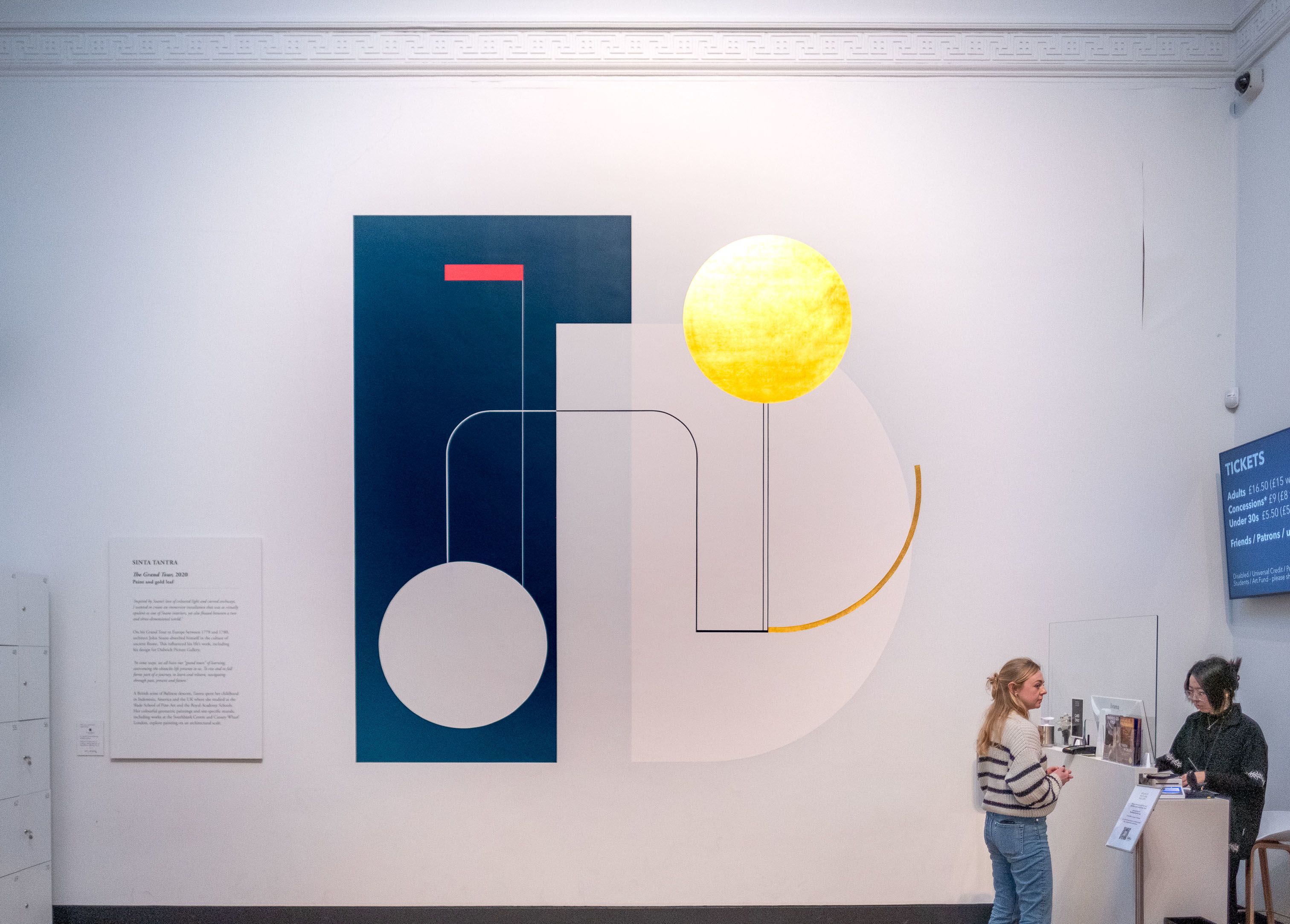

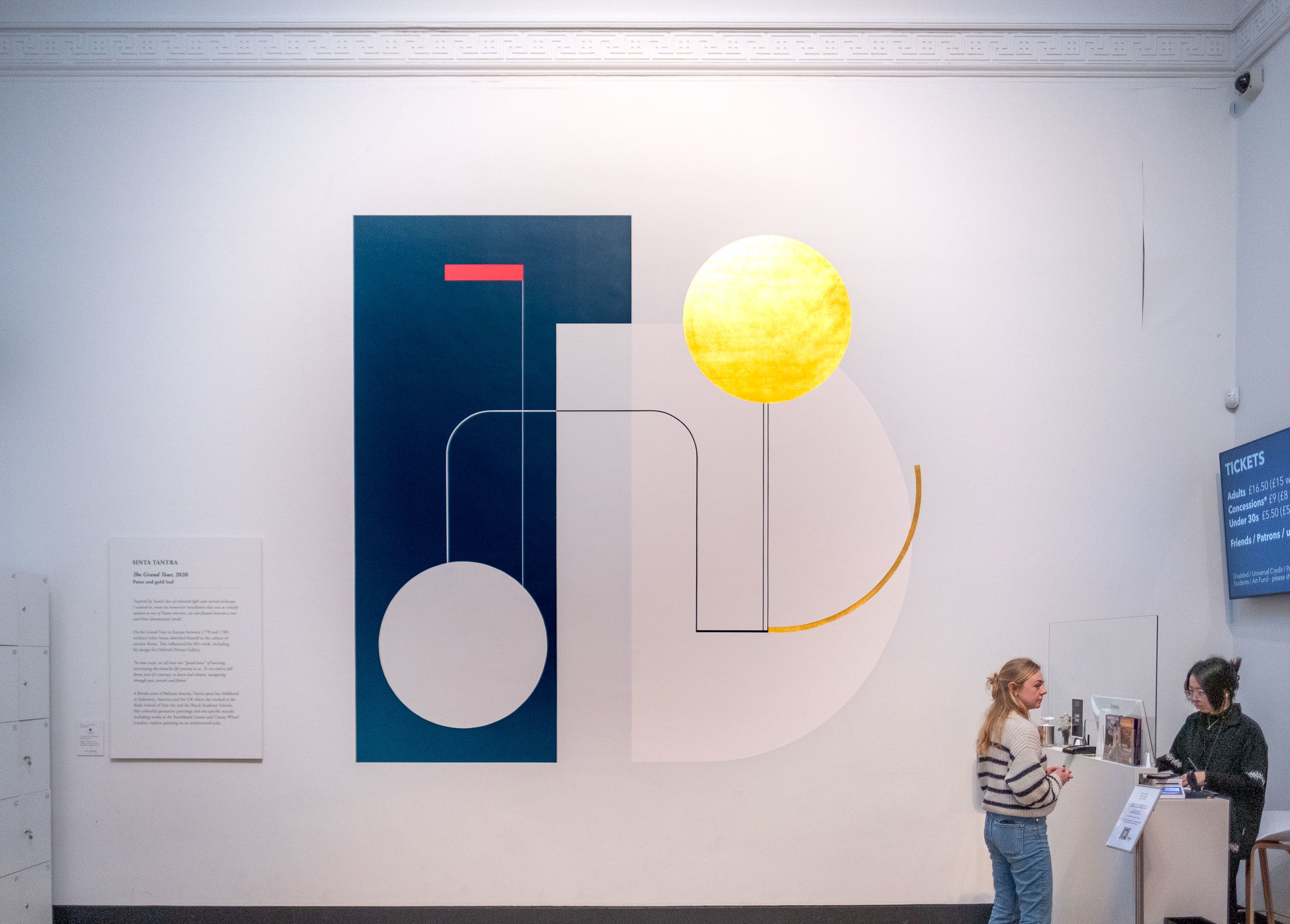

Dulwich Picture Gallery:

Degrees of Separation

top-knot ticket: one /

shape of us in magnitude

a tone-deaf tour, grand

poets's note:

This mural by Sinta Tantra, entitled ‘The Grand Tour’ welcomes visitors to the redesigned open plan entrance to Dulwich Picture Gallery. You don’t need a top-notch golden ticket to enter; art is for everyone. The midsection of this mini is a personal nod to that (worst) of Ed Sheeran songs, ‘Shape of You.’ Somehow, I always mishear the line ‘push and pull like magnets do’ as ‘push and pull in magnitude’ and that, to me, is what it feels like to walk around an art gallery. Sometimes, our magnified thoughts and feelings are seen in shapes: of someone or something we’re missing. Is this viewer feeling that? Who or what is reflected back at her as she makes her way through the museum? ‘Tis a mystery, to be sure. Finally, as well as being a fairly obvious reference to the title of the mural, the tour is tone-deaf because of the misheard earworm and the inability of an audio guide to capture these multitudes of meaning.

how did I get here?

life passes before all eyes

we stay, they go – next!

poets's note:

The viewers in this picture are looking at Rembrandt’s ‘Girl at a Window.’ The photographer is looking at them, I’m looking through him, and, thanks to me, you’re looking at all the above – trippy. Meanwhile, the Girl at the Window – like her fellow portraits – sees it all as people pass her by: from easy chats to existential crises. I can’t make up my mind which these two are feeling; can you? The final line is a nod to the intense memento mori vibes from the man on the far left (literally, Portrait of a Man). Life goes on.

see and seen; all that

heard yet unspoken; hush, hush

let me sit; just be

poets's note:

Same painting; totally different thoughts. Perhaps because I’ve already written about this ‘Girl at a Window’ it feels like there is nothing more to say: yeah yeah, she sees and is seen, we get it. For me, the end clauses are also quite a personal response to the slightly woo/woke phrases evoked in the first halves. Though the sentiment is, ironically, the same, the overwhelming feeling I get – through the conduit of this slightly more slumped sitter – is of not wanting to feel seen or heard, but to be left alone.

hey there, look at that

suddenly I see – at source

my strength, ever She

poets's note:

I can’t explain why (my gut blames 80s/90s American movie culture) but something about this figure just screams “well, would ya look at that!” What is it? the haircut? the tourist pants? the glasses with beard? the thumbs in belt loops? Who knows, but it is loud. Anyhoo, this impressive oil on canvas is ‘Samson and Delilah’ by Van Dyck. We all know the story, I won’t repeat it.

Apart from the old testament assembly thang, I always think of the song ‘Hey there, Delilah’ by the Plain White T’s – I remember it was one of the songs that my brother used to play at hyperlocal music festivals. Yes, it must have been around that time because I also associate it with KT Tunstall’s ‘Suddenly I See’ which played on repeat in my friend Laura’s silver Ford KA as she ferried us from A Level Theatre Studies to the RST and back in pursuit of actors I daren’t name here. And so, because that’s what poets do, I put two and two together: mixing fangirl beats with the assumed romantic realisation of a total stranger.

what is a daughter?

eyebrows express abstract; an

interpretation

poets's note:

This scene depicts a (presumably, our minds like to fill in the gaps) mother and daughter wandering into Anthony Daley’s Son of Rubens exhibition, which recently closed. It’s a response collection: the painter has taken inspiration from 17th century Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens to create an interpretive body of work that is both familiar and new. Reading this, it struck me how much our children are interpretations of ourselves. I have two sons, so while I can’t speak directly to the relationship in this picture, there is something relatable in the twin direction of their brows and gaze. I know that this, too, is one of the key physical traits I share with my children. Since they were tiny they have interpreted the world around them and communicated it to me through eyebrow expressionism – often at inopportune moments like a supermarket checkout queue.

late fête champêtre:

revelry in a raincoat

cerebra thunder

poets's note:

I’ve extrapolated a glorious amount in this one, and I adore the fact that I might be either spot on or a million miles away from the truth. The most wonderful thing is that it doesn’t matter anyway. The picture that this viewer is looking at is ‘A View of Walton Bridge’ by Canaletto. Knowing this alone triggers a symbolic state of mind, particularly when we consider the coat held in unconscious preparation.

But then, to the left, we have ‘Fête Champêtre’ by Jean-Bapiste Pater; a garden party in pastel pink. Knowing this, a (more highly relatable) situation fictionalises for me. An outdoor social gathering, full of “fashionable types” in “deep in conversation”, has suddenly become too much – it has started raining, and I/the character can no longer mask amid the faux-festivities. Instead, I/the character escape to the silence and safety of a nearby art gallery. Canaletto, painter of the bridge circa. 1754, was said to be particularly adept at portraying shifting English weather.

Meanwhile, an amateur poet 250 years later, is mildly adept – thanks to a thorough Grammar School grounding in PATHETIC FALLACY and its ilk – at connecting these internal/external meteorological symptoms: a cluster headache, brought on by social overwhelm.

walking talking dolls

wheeling through each other’s worlds

sim-plicity slides

poets's note:

Cripes there’s a lot to talk about in this one. Part of me doesn’t even believe that it’s accidental; the placement is just too perfect. Suspending disbelief for a moment, this lady sits quite literally between two worlds: her chair positioned at the intersection of a collection about ageing and an exhibition on universal transition. She reminds me of a Barbie doll; if Barbie did an age-positive art curationism range. Or an EA Sims character who has reached level 10 of the ‘painter’ career path: Master of the Real.

One of the great European Symbolists, Lithuanian artist M.K. Čiurlionis uses structure and colour to draw lines between mythology and reality. In capturing this perfect moment, Vincent Dupont-Blackshaw has done something similar. And, in my own, much removed way, I too have played with this cross-dimensional feeling. Here, art, photography, and poetry are each a kind of walkie-talkie tool through which we can communicate through space and time. Pretty cool.

a mythless man sends

tempera text: where r u?

in another world

poets's note:

More Čiurlionis: I really wish I’d been able to see this exhibition. His work is prolific: painting hundreds of works in just a few short years to the point of burnout by feverish creativity. Let’s just say I can relate. Many of his paintings use the tempera technique, which served its alliterative purpose here if nothing else. Got a bit lost in reading the contextual copy around this one: apparently Čiurlionis also had synaesthesia (which I don’t, but fascinates me all the same) which presumably helped him to better translate ethereal ideas about escape and longing in image. Anyway, this is a self-explanatory haiku: here she is, just trying to escape through art, badgered by a faceless somebody, insisting she comes back home, to earth. Yawn.

o, this precious time

queen of stolen lunch / breaks, for

her work is not done

poets's note:

The third and final Čiurlionis. This painting, Rex, is dated 1909. A Lithuanian abstract icon, the piece itself speaks to that broadest of artist issues – mankind’s relationship to the universe, oof. And yet this poem isn’t about mankind, it's about womanhood; 1909 was also the year that Marion Wallace Dunlop became the first imprisoned suffragettes to go on hunger strike. The viewer in this picture stands in front of Rex, a kinglike figure with a crown and long white beard who guards a part Midsummer Night’s Dream, part Middle Earth-esque landscape. It’s corny, but as a Stratford girl I get an immense satisfaction from shoehorning secret Shakespearean syntax. Here, it’s hidden in plain sight in the opening vowel – a reference to that famous Fairy Queen Titania’s ‘O, how mine eyes do loathe his visage now!’

Clearly, the plain-English interpretation I’ve made here is that this woman is on a lunch break. The final line is more ambiguous: has she got an unchecked to-do list waiting at her desk or does she feel the weight of the patriarchy loom over her? It’s also a personal reference to something that my yoga teacher says at the end of her (dreamlike) sessions, just as we settle into our final resting poses. We relax the space between our eyebrows, take a groupbreath, and sigh = all the work is done. Except when it’s not.

is this peace? carpels

contain wisesacs fruited with

friendship al fresco

poets's note:

This is such a cute scene. I can’t work out if the little girl and the lady know each other or not, but it hardly matters. The fact that they are mutually experiencing this moment of quiet companionship in front of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s 1733(ish) highly decorated masterpiece prompted parallels in plural. While the central fresco depicts an Old Testament scene in which Pharaoh's ring is bestowed upon Jason Donovan Joseph, the foreground is filled with the kind of cross-generational contentment in which something more meaningful is given: time, attention. I wanted to find a way to bring the lavish jewels of the painting into the poem, and the too-good-to-be-true accents of Jason Donovan Joseph’s tangerine-coloured coat reflected in the lady’s San Francisco tote provided. From there, I connected the segments (via a wormhole learning pathway into the individual parts of a satsuma) and voila: a perfect pairing.

let them have their nights

but they will not take my day

extinguish us not

poets's note:

Honestly, the jury is still out on this poem; mainly because it is so far and away my favourite photograph in the collection I was very nervous about spoiling it with my own whatever-words. But, for those of you who are still reading these self-indulgent asides, here’s what I did. A man (older, we can admit) is sitting, eyes closed, just around the corner from an inconspicuous yet iconic painting: Jacob de Gheyn III by Rembrandt. It’s not one of Rembrandt’s most famous paintings – that would be the Night Watch, which unlike this one I have actually seen in person once, in Amsterdam’s RijksMuseum. No, this particular portrait is perhaps most famous as the world’s most stolen painting – likely due to its diminutive size. As far as I can tell (ie: as far as Wikipedia tells me) its last theft was in the 1980s; which, if I’m not being too presumptuous, was quite possibly the last time the photograph’s other subject felt capable of an Ocean's 11 style art heist. You can see what I did here: stolen painting, stolen life, yada yada – compared to the beautiful symmetry between the portrayed ruffs and the seated tufts of white hair it’s clumsy, but I went there. Finally, a special shout out to the precision positioning of the literacy fire extinguisher here for providing a finisher. Ever so grateful.

triple-faced filters

forgotten fizz-mongering

knotted to the spot

poets's note:

A room full of faces. The three central faces are Mrs. Elizabeth Moody with her two sons, Samuel and Thomas. They were painted in after her death, which perhaps explains her inattention. To the left, the gentleman in red – identified by Google Lens as Portrait of a Man – was reluctantly painted by William Hogarth as one of many jobbing portraits in a loathsome trend he called ‘phiz-mongering’. Though it provided a steady stream of income to subsidise the more moral ‘beat’ of landscape painting, he became increasingly infuriated with the self-obsession of this popular practice. So what we have here is not just a room full of faces but a room full of fizzes, forgotten in time and place. Of course, it’s easy to draw lines between this early portraiture and selfie-culture – and, because it’s easy, that’s exactly what I’ve done. The ‘triple-face’ is a kind of throwaway reference to a self-portrait by Sylvia Plath; even this more three-dimensional and self-aware visual bears its own filters. Meanwhile, ‘knotted to the spot’ bears its own triptych of thoughts, too: a) forget-us-knot, they say; b) they cannot move from their fixed abodes; c) I cannot get up from the desk and watch MAFS Australia until this poem is writ.